As you may recall from part two, fashion sewing patterns were still rather complicated in the mid-1800s. However, some, like Ellen Louise Demorest and her husband William Jennings Demorest, began to assist those who were interested in sewing at home — assisting at a profit, of course.

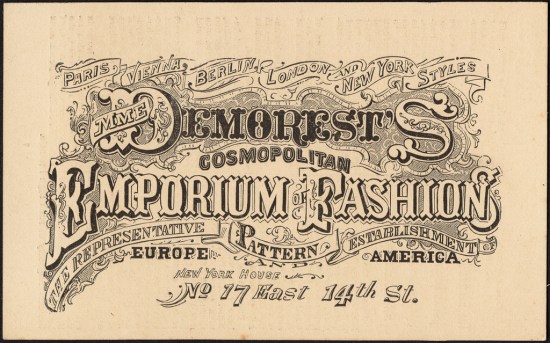

By 1860, Madame Demorest’s Emporium of Fashion began advertising her patterns in magazines. This was still by-hand work, with the patterns cut to shape in two options for the consumer: purchased “flat”, which was the cut patterns folded and mailed, or, for an additional charge, “made up” which had the pattern pieces tacked into position and mailed. At this time, Madame Demorest’s Emporium of Fashion used fashion shows held in homes, along with trade cards, to promote her patterns — as well Demorest publications. In 1860, the Demorests began publishing Madame Demorest’s Mirror of Fashions, a quarterly which not only featured plates of their own dress patterns but included a pattern stapled to the inside as well. However, patterns were still only available in one size at this time.

The beginning of sewing patterns as most of us know them has its roots in the winter of 1863. According to The Legend, Ellen Buttrick and her complaint were the mother of invention; but it was her husband, Ebenezer Butterick, an inventor and former tailor, who revolutionized sewing patterns and fashion history in the winter of 1863.

Snowflakes drifted silently past the windowpane covering the hamlet of Sterling, Massachusetts in a blanket of white. Ellen Butterick brought out her sewing basket and spread out the contents on the big, round dining room table. From a piece of sky blue gingham, she was fashioning a dress for her baby son Howard. Carefully, she laid out her fabric, and using wax chalk, began drawing her design.

Later that evening, Ellen remarked to her husband, a tailor, how much easier it would be if she had a pattern to go by that was the same size as her son. There were patterns that people could use as a guide, but they came in one size. The sewer had to grade (enlarge or reduce) the pattern to the size that was needed. Ebenezer considered her idea: graded patterns. The idea of patterns coming in sizes was revolutionary.

By spring of the following year, Butterick had produced and graded enough patterns to package them in boxes of 100, selling them to tailors and dressmakers. These early Butterick patterns were created from cardboard. However, as most early patterns were sold by mail, heavy cardboard was not ideal for folding and shipping. Butterick experimented with other papers, including lithographed posters (printed by Currier and Ives). While these were easier to fold and ship than cardboard, they were still not ideal. Ultimately the search lead to less expensive and light-weight tissue paper.

For the first three years, Butterick patterns were for clothing for men and boys; in 1866, Butterick began making women’s dress patterns. This is when the sewing pattern business really began to grow. In order to promote the mail order patterns, Butterick began publishing The Ladies Quarterly of Broadway Fashions (1867) and the monthly Metropolitan (1868).

Madame Demorest’s Emporium of Fashion was still going strong, as was their publication. Although the magazine was expanded to include a lot more magazine content as Demorest’s Illustrated Monthly Magazine and Madame Demorests Mirror of Fashions in 1864. In 1865, the name was changed again, this time to Demorest’s Monthly Magazine and Demorest’s Mirror of Fashions — more commonly referred to as Demorest’s Monthly. This monthly was reaching over 100,000 readers.

The success of sewing patterns could not be ignored and the competition would really begin; by 1869, James McCall started his pattern business.

These early sewing patterns by Butterick, McCall’s, and Demorest were not printed, but rather outlined on the tissue paper by a series of perforated holes. They were typically sent in an envelope which had a sketch of the finished garment and brief instructions printed on it. These instructions included suitable fabric suggestions, size information, and a description of how the pieces were to be cut from the tissue and pieced together to form the garment (assisted by a code of shapes, such as v-shaped notches, circles, and squares, which were cut into the paper).

In 1872, Butterick began publishing The Delineator. As with the earlier publications, The Delineator was originally intended simply to market Butterick patterns. However, it quickly expanded into a general interest magazine for women in the home, offering everything from fashion to fiction from housekeeping to social crusading (including lobbying for women’s suffrage in the early 1900s). As readership skyrocketed, the earlier publications were folded into The Delineator — and the magazine would go on to become one of the “Big Six” ladies magazines in the USA.

In 1873, McCall’s would start their own publication called The Queen. In 1896, the name was changed to The Queen of Fashion and it would be the first magazine to use photographs on its cover.

In 1875, the first in-store sewing pattern catalogs appeared. These were produced by Butterick.

Madame Demorest was still around. In addition to marketing paper patterns through the magazines, the patterns were sold through a nationwide network of shops called Madame Demorest’s Magasins des Modes. In addition to the paper patterns and drafting systems, the shops sold ready-made fashion items, Demorest’s line of cosmetics and perfumes, and custom dressmaking services to wealthy clients. It was the latter, along with fashion exhibitions in London and Paris, which really boosted the designer and therefore the company’s profile. By the mid-1870s, there were 300 Demorest shops, employing 1,500 sales agents. Her employees were mainly women, including African-American women who received the same treatment as the white women workers.

In 1877, business was peaking. The Demorest’s Monthly began circulation in London and, along with the quarterly, the company began publishing Madame Demorest’s What to Wear and How to Make It. Just a few years later, however, Demorest business declined. This was unfortunately do to the Demorests’ failure to patent their patterns, allowing themselves to be bested by competition. In 1887, Demorest sold their pattern business, which went on to live on primarily in name only — including sewing machines.

To Be Continued…

Image of Mme. Demorest Hilda Polonaise Pattern via dakotanyankee; image of 1899 Butterick Pattern Ladies Double Breasted Coat via janyce_hill.